Parasites as drivers of host diversification, including domestication

© 2026 Bio Communications

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Parasites are ubiquitous evolutionary agents that, among other things, drive the diversification of hosts. This could also apply to animal domestication, one of the most striking evolutionary processes generating phenotypic diversity, which has recently been proposed as a parasite-mediated process (“The parasites-mediated domestication hypothesis”, PMD). The PMD is based on the fact that parasites can alter the (neuro)endocrine system (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, gut-brain axis, thyroid secretion, etc.), influence gene expression and ontogenetic systems, including neural crest cell development, and thus modulate physiological, behavioural and developmental components underlying the domestication. In this article, domestication is therefore placed in the context of parasite-driven diversification. The rationale for the parasite-mediated domestication process and associated diversification is supported by explanations of possible underlying mechanisms in light of the pioneering work of the Belyaev fox experiment and the later proposed hypothesis on the role of neural crest cells. Finally, a framework for plausible comparative and experimental approaches to test the PMD is proposed. Placing domestication in the context of the parasite-driven host diversification process provides a broad perspective for future research in the field of animal evolution and domestication.

Keywords:

Parasitism, Domestication, Diversification, Evolution

1. Introduction

Interactions between species shape the course of evolution, with parasitism being one of the most ubiquitous antagonistic interspecific interactions that has a decisive influence on evolutionary processes. Parasites influence not only micro- but also macroevolutionary processes, including diversification (Zeng & Wiens, 2021; Hasik et al., 2025). In animals, parasitism has also been shown to be a key interspecific interaction that promotes large-scale patterns of animal diversification (Jezkova & Wiens, 2017), and domestication can be considered as such.

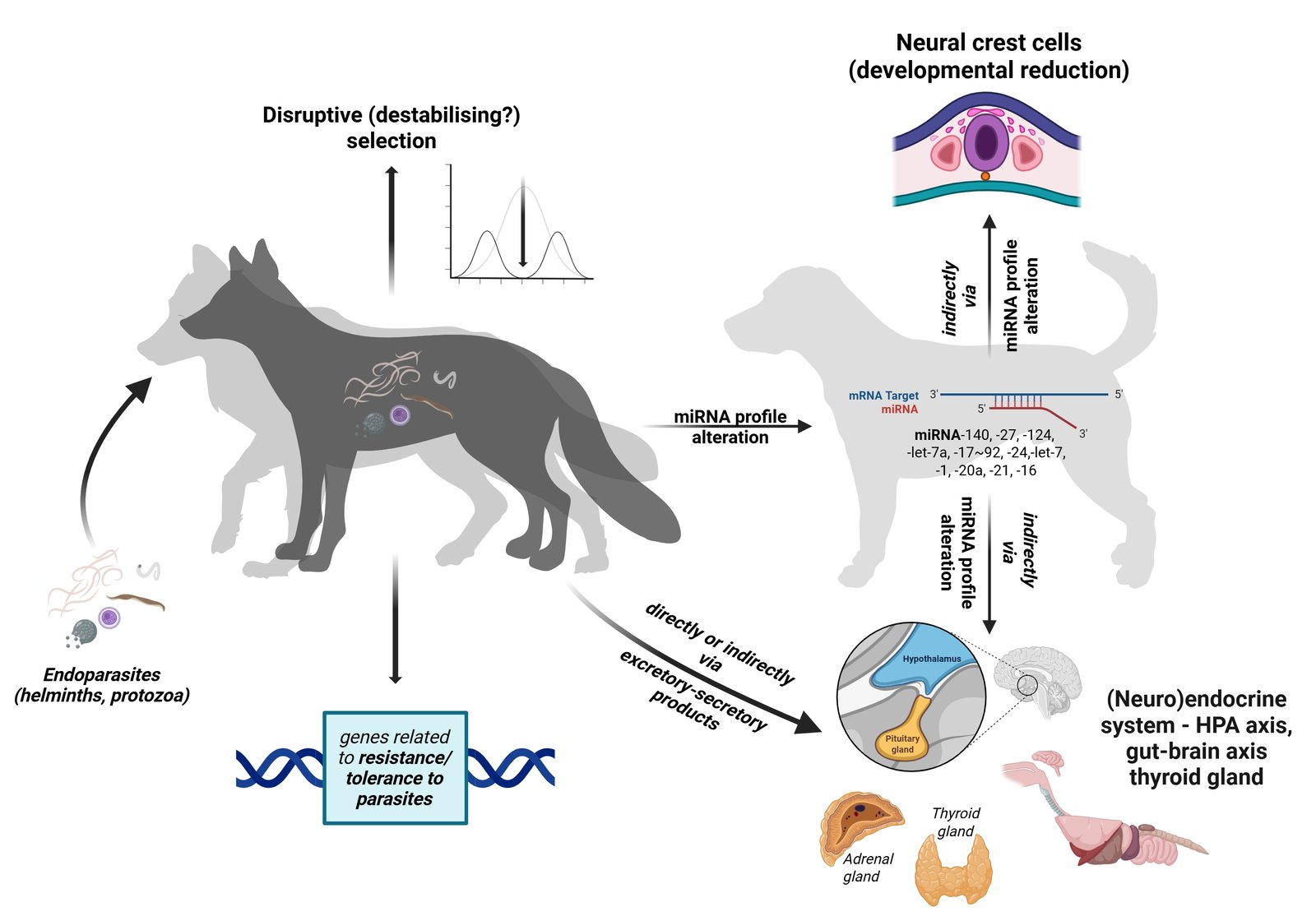

The recently proposed 'parasite-mediated domestication hypothesis' (PMD) follows this premise very well. Namely, PMD assumes that the domestication process in animals, with the associated diversity of domestication phenotypes, has a common cause in (endo)parasites (Skok, 2023). PMD predicts that the frequency of domestication syndrome (DS) traits, such as tameness, floppy ears, short and upturned tail, depigmentation, etc., in the wild population increases with increasing parasite susceptibility (higher parasite load). PMD stems from the fact that endoparasites intervene in the modulation of all important mechanisms and processes that play a role in the domestication of animals (Table 1). Indeed, parasites are able to alter the (neuro)endocrine system (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, gut-brain axis, thyroid secretion, etc.) and thus influence host physiology and behaviour, gene expression and ontogenetic systems, including neural crest cell development, either directly or indirectly via their excretory and secretory products. According to PMD, parasites therefore ultimately prepare the ground for one of the most striking evolutionary processes generating phenotypic diversity, be it in terms of behaviour, morphology or physiology (Trut & Kharlamoba, 2020).

| Parasite-induced changes | References |

|---|---|

| Behaviour | Poulin, 1994; Poulin & Thomas, 1999; Poulin, 2010; Thomas et al., 2010; Kaushik et al., 2012; Adamo, 2013; Poulin, 2013; Del Giudice, 2019; Gopko & Mikheev, 2019; Hughes & Libersad, 2019; Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022; Hernandez-Caballero et al., 2022; Nadler et al., 2023 |

| Morphology | Sandland & Goater 2001; Duffy et al., 2008; Blanchet et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2010; Gopko & Mikheev, 2019; Hernandez-Caballero et al., 2022; Nadler et al., 2023 |

| Hormone / neurotransmitter secretion | Bagnaresi et al., 2012; Kaushik et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018; O'Dwyer et al., 2020; Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022 |

| Gene regulation | Nuismer & Otto, 2005; Matthews & Phillips, 2012; Sharma, 2014; Barribeau et al., 2014; Cheeseman & Weitzman, 2015; Feldmeyer et al., 2016; van Otterdijk & Michels, 2016; Wijayawardena et al., 2016; Nadler et al., 2023; Buck et al., 2014; Weiner, 2018; Paul et al, 2020; Antonaci & Wheeler, 2022; He & Pan, 2022; Rojas-Pirela et al., 2023; Chowdhury et al., 2024 |

The process of (proto-)domestication, with the associated phenotypic variability and underlying developmental mechanisms was the focus of the pioneering work of Belyaev (1969, 1979; silver fox experiment, destabilising selection) and the later complementary explanations of Wilkins et al. (2014; deficits in neural crest cells during embryonic development) – both will be discussed in more detail later. However, the PMD attempts to further complete the picture by proposing an initial "proto-domestication" trigger for the modulation of these mechanisms/processes and thus for the developmental changes that then lead to domestication.

Placing domestication in the context of the role of parasites in the evolution and diversity of animals opens up new perspectives not only for the study of domestication, but also for the evolution and diversity of animals in general.

2. Earlier explanations of the mechanisms of domestication and the resulting phenotypic diversity

In chronological order, the seminal studies of Belyaev (1969, 1979) introduced the concept of destabilising selection by establishing that selection for tame behaviour leads to the breakdown of previously integrated ontogenetic systems, resulting in multiple phenotypic effects that do not appear to be genetically linked to the selected trait. According to Belyaev, selection for tameness thus appears to have a direct or indirect effect on the neuroendocrine control systems of ontogenesis and is therefore responsible for the domestic phenotype (tameness, floppy ears, short and upturned tail, depigmentation, etc.), known as domestication syndrome. Belyaev (1979) goes on to suggest that destabilising selection could disrupt the normal patterns of gene activation and inhibition and lead to a sharp increase in the range and rate of heritable variation. Under the influence of an altered hormonal balance, a number of "dormant" genes could be expressed, leading to a high frequency of occurrence of a whole complex of morphological traits (position of the tail, ears, etc. – and other characteristics of DS). He also claimed that this always seems to be the case when new stress factors appear in the environment or when stress factors common to the species increase in intensity - nowadays it is generally recognised that stressful conditions promote evolutionary changes (Love & Wagner, 2022).

Much later, Wilkins et al. (2014) expanded on Belyaev’s findings in their neural crest cell hypothesis, suggesting that initial selection for tameness leads to a reduction in neural crest-derived tissues of behavioural relevance via multiple pre-existing genetic variants (consisting of mutations with a semi-dominant or ‘stand-alone’ neutral effect), and that no single 'domestication' gene mutants have been found to mimic the entire DS phenotype, but rather that the changes are quantitative. They concluded that the initial domestication changes may not be DNA sequence alterations, but epigenetic changes (i.e. epimutations).

3. Mechanisms of the domestication process in the light of parasitism as a driver of host diversification

The domestication syndrome and intraspecific phenotypic diversity of domestic animals, as well as the underlying mechanisms described by Belyaev (1969, 1979) and Wilkins et al. (2014), can all be caused by parasites (Fig. 1, Table 1 and 2).

| Mechanisms/systems involved | Affected traits associated with DS |

|---|---|

| NCCs development | ear, tail (chondrogenesis and bone development), skull morphology (craniofacial and bone development), pigmentation (pigment cells), and general neural crest induction/specification |

| Gut-brain/HPA axis | tameness/aggression, explorative behaviour, fear/stress response, prosocial behaviour |

| Thyroid gland function | heterochrony (e.g. pedomorphysm) |

| DS, domestication syndrome; NCC, neural crest cells; HPA, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal | |

3.1. Parasite-mediated (neuro)endocrine function, immune response and behaviour

Essentially, Belyaev’s fox experiment was based on the variability of a certain behavioural trait, namely the reaction to humans (tameness). About 10 percent of the initial wild population displayed relatively tame, non-aggressive behaviour, which he described as a 'quiet exploratory reaction without either fear or aggression' and which was eligible for domestication (Belyaev, 1979). To get straight to the point, here is the first possible link to parasites, because it is known that many parasites alter the behaviour of their hosts in such a way that the probability of transmission increases (Poulin, 2010; Adamo, 2013; Poulin, 2013; Del Giudice, 2019; Hughes & Libersat, 2019).

Parasites influence behaviour via the gut-brain/HPA axis and, for example, alter the secretion of glucocorticoid hormones (GC) and thus modulate animal stress and fear response of animals. In fact, GC secretion increases with the intensity of the stress or fear response, with domestic animals generally having lower GC concentrations compared to their wild counterparts (Karaer et al., 2023). Although parasite infection often leads to an increase in GC concentration, parasite-induced GC secretion varies greatly depending on the phase of parasite infection and parasite taxa (O'Dwyer et al., 2020).

In addition, parasites also influence animal behaviour by altering the levels of neurotransmitters (Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022), for example noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine (all of which also act like hormones).

The variability of serotonin and melatonin secretion was also given special consideration by Belyaev (1979), with the tamest animals showing higher levels of these hormones/neurotransmitters. Most studies have shown that serotonin increases when infected with endoparasites (reviewed in Wang et al., 2018) - in any case, there are only a few contradictory studies (e.g. Helluy & Thomas, 2003; Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022). Serotonin is known to influence immunity and plays a very important role in animal behaviour, including the promotion of prosocial behaviour and the inhibition of the fear response. It is suggested that the changes in host behaviour could be related to parasite-induced changes in brain monoamine levels, including serotonin signalling in the brain (Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022).

The situation with melatonin is somewhat more complex, but not to be neglected, because melatonin certainly plays an important role in the host-parasite relationship. In fact, there are many unique adaptations that involve intricate links between melatonin and the biology of the parasite-host relationship – either as a protector of the host or as a tool that can be exploited by the parasite (Bagnaresi et al., 2012).

Dopamine, another important neurotransmitter and a hormone that is also responsible for behavioural modulation, including fear memory extinction (Frick et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2025), has also been shown to be altered by parasites. For example, some protozoan parasites (e.g. Toxoplasma gonadii) produce dopamine in their cysts (Kaushiket al., 2012), while helminths could indirectly influence dopamine secretion via effects on the host microbiome and immune response (Blecharz-Klin et al., 2022) – dopamine is also recognised as an important immunomodulator with receptors expressed on a variety of immune cells (Gopinath et al., 2023).

By altering the function of the host's immune system and neuroendocrine system, gut-brain/HPA axis, etc., endoparasites generally influence animal behaviour to reduce fear responses, promote prosocial behaviour and thus enhance inter- and intraspecific contacts. In other words, endoparasites often make animals tamer and more exploratory. So, if we stick strictly to the PMD baselines, at least the initial population of tamer foxes from Belyaev’s experiment should be more susceptible, i.e. less resistant and more tolerant to parasites (with higher parasite load, richness/abundance; especially endoparasites - helminths and protozoa). Accordingly, we can assume that the current experimental population of silver foxes (or minks subjected to similar selection on the same experimental farm, see e.g. Trapezov, 1987) differ in their susceptibility to parasites depending on the degree of tameness/domestication, with the lineages of the tamest animals being more susceptible to parasites (e.g. higher parasite load) than the animals of the aggressive (“wild”) lineages.

3.2. Parasites-mediated destabilising selection

As for destabilising selection, which is a central concept of Belyaev’s domestication model, parasite infection can often cause a very similar shift in the mean value of a phenotypic trait and increase phenotypic variation in the host population – in a vertebrate host, the impact is often proportional to the severity of the infection (Poulin & Thomas, 1999). Another very similar phenomenon is disruptive or diversifying selection, which favours different phenotypes in different parts of an interbreeding population and, as has been shown, can also be caused by parasite infection (Duffy et al., 2008; Blanchet et al., 2009).

3.3. Parasite-mediated genetic and epigenetic factors

Ultimately, Belyaev (1979) claimed that destabilising selection, and thus the domestication syndrome, is a manifestation of the activation of a number of “dormant” genes, i.e. that several existing alleles contribute to the response to selection for tameness; this was supported by the assertion, that such simultaneity if mutations at structural loci were the cause of these traits is statistically unlikely. So, as Wilkins et al. (2014) noted, Belyaev was actually talking about the process now known as epigenetic changes, i.e. epimutations which later become heritable, fixed genetic changes. And epimutations have been shown to be transgenerational transmissible/inheritable (Morgan et al., 1999; Rakyan et al., 2003; van Otterdijk & Michels, 2016; Fitz-James & Cavalli, 2022).

There is much evidence to suggest that the genetic and hereditary basis of phenotypic changes in domestication and the underlying mechanisms explained by Belyaev (1969, 1979) and Wilkins et al. (2014) may be related to the role of parasites. Although PMD suggests a possible relationship between the genes for parasite resistance/tolerance (e.g. the genes of the major histocompatibility complex, MHC, which also mediate various behaviours – discussed e.g. by Ruff et al., 2012; Hasik et al., 2025) and the domestication syndrome, including the genes responsible for it, the epigenetic machinery is central to PMD anyway (Skok, 2023).

As for Belyaev's suggestion of stress as a trigger for the expression of “dormant” genes, parasites, which are above all a ubiquitous stressor in the environment, can be an important agent in such epigenetic processes. Most environmental factors and stressors, including pathogens, endocrine disruptors etc. have the capacity to alter the epigenome resulting in phenotypic variation that can be subject of an epigenetic transgenerational inheritance (Matthews & Phillips, 2012; Sharma, 2014; Skinner, 2014; van Otterdijk & Michels, 2016). This also applies to parasite-induced stress, which often shapes the development and phenotype of animals, including behaviour. Therefore, transgenerational programming of parasite-induced stress pathology should not be neglected in the causal model of domestication and host diversification in general.

Finally, and potentially of considerable importance, microRNAs or miRNAs with the parasite-induced changes in the host miRNA profile may have played a crucial role in host diversification, including the initial development of the domestication syndrome. miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that are, among other things, important inter- and extracellular signalling molecules and significantly regulate gene expression (Gurtan & Sharp, 2013; Xu et al., 2013). In humans, a self-domesticated species, for example, half of the transcriptome is subject to miRNA regulation, which means that this post-transcriptional control pathway influences almost every major gene cascade (Pasquinelli, 2012). miRNAs are thus significantly involved in many prenatal and postnatal developmental and physiological processes (Floris et al., 2016) and are involved in epigenetic regulation as part of the epigenetic machinery (Yao et al., 2019).

The miRNA profile of the host and thus the regulation of cell processes is inevitably altered by a parasite infection (Judice et al., 2016; Paul, 2020; Rojas-Pirela et al., 2023; Chowdhury et al., 2024). Parasites excrete and secrete various products through which they can alter the expression of miRNAs in the host by either upregulating or downregulating certain miRNAs (Zheng et al., 2013; Judice et al., 2016). However, parasites also contribute to the miRNA profile of the host by secreting their own miRNAs, often through the secretion of miRNA-containing vesicles into host cells (Buck et al., 2014). Parasite-derived miRNAs, which have the same regulatory functions as their hosts' miRNAs, have recently been recognised as the main means by which parasites manipulate their hosts (Chowdhury et al., 2024). It is important to note at this point that parasites excrete and secrete many other molecules besides miRNAs, such as signalling proteins, short-chain fatty acids, etc. (Coakley et al., 2016; Rojas-Pirela et al., 2023), that could also be involved in all other PMD pathways.

As described in PMD (Skok, 2023), there are several miRNA families involved in the development of NCC as well as parasitic diseases caused by endoparasites (e.g. miRNA-140, miRNA-27, miRNA-124, miRNA-let-7a, miRNA-17~92, miRNA-24, miRNA-let-7, miRNA-1, miRNA-20a, miRNA-21). However, there are no studies on the direct effect of parasites infections on the neural crest cell development, so in this context, conducting experiments to clarify this issue should be prioritised. In addition, several miRNAs are also involved in the activity of the (neuro)endocrine system and the regulation of hormone production, activity and responsiveness of target cells and thus hormone concentrations (miRNA-21, miRNA-let-7, miRNA-16 and miRNA-24; Park, 2017), which is one possible way in which parasites manipulate host (neuro)endocrine function and behaviour. However, as miRNAs play a major role in epigenetic regulation of gene expression (Yao et al., 2019) and the miRNA profile involved in the development of NCC, (neuro)endocrine function and parasitic diseases overlaps significantly, these small non-coding RNAs are a serious culprit for host diversification, including domestication.

Wilkins et al. (2014) have also highlighted several genes that may be critical in reducing, delaying and modifying the development and migration of NCC. These include, for example, Pax genes, which are essential for the differentiation of several neural crest derivatives (Monsoro-Burq, 2015). At the transcriptional level, the timing of PAX gene expression during development and PAX gene translation are also regulated by various miRNAs with tissue-specific expression patterns (Shaw et al., 2024), with miRNA often leading to repressed target gene expression (Pasquinelli, 2012). Indeed, the same mechanism of miRNA-mediated gene regulation may apply to all other "neural crest cell genes" (e.g. SOX genes, etc.) listed by Wilkins et al. (2014), as well as to other genes associated with domestication syndrome.

4. Plausible methodologies to examine the role of parasites in domestication

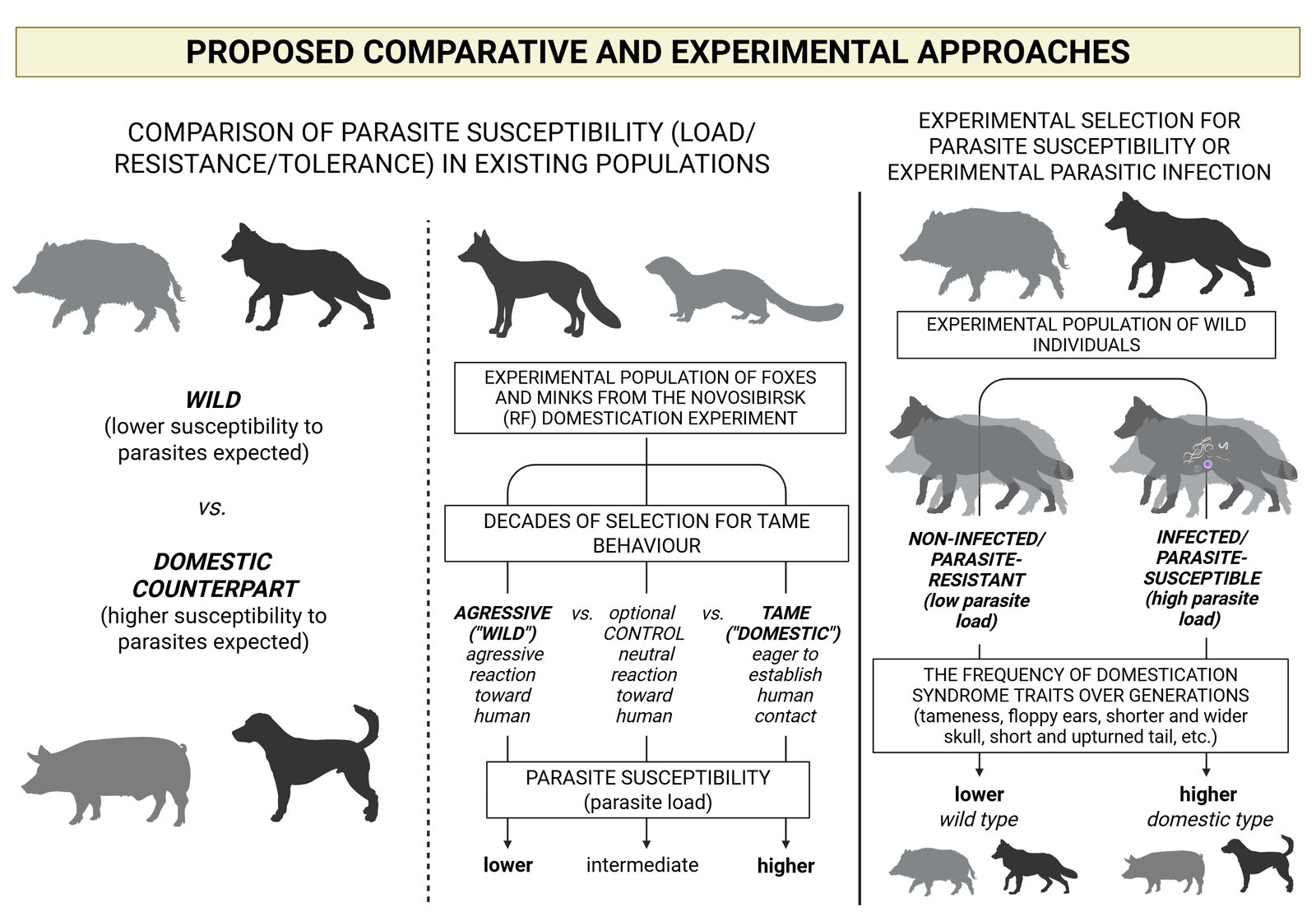

Testing hypotheses about the role of parasites in species diversification, speciation and extinction poses a number of methodological challenges (Hasik et al., 2025), and similar challenges apply to testing the role of parasites in proto-domestication (PMD). There are two basic approaches to testing PMD. The first and easier to implement are comparative methods, the second, but much more difficult to implement, are experimental methods (Fig. 2).

4.1. Comparative approaches to testing PMD

Comparative approaches should inevitably include existing populations of domesticated species. Firstly, by analysing the differences in parasite susceptibility of today's free-ranging domestic animal populations compared to their wild counterparts from geographically close areas (see the first study of this kind on the pig by Oleinic et al., 2023). With regard to PMD, it can be assumed that domestic animals are more susceptible to parasites (have a higher parasite load) than their wild counterparts, as Oleinic et al. (2023) also found. However, this approach has some drawbacks, e.g. uncertainties related to the genetic background of the host, especially in the wild animal cohort, and environmental confounders (e.g. due to specific conditions at different microsites, etc.), even if animals from a comparable environment are sampled.

Therefore, currently the most efficient and feasible test for PMD would be the comparison of parasite susceptibility of different classes in relation to tameness (degree of domestication) of foxes and minks from the domestication experiment in the experimental farm of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia (Belyaev, 1969; Trapezov, 1987; Trut, 1999). Decades of systematic selection for tame behaviour have produced numerous lineages that cover the entire phenotypic gradient from aggressive/wild to completely tame animals. Therefore, the Novosibirsk fox/mink population would be an ideal place to testing PMD. In addition, the animals have lived in the same controlled environment all the time and have a clear genetic background, so that any drawbacks related to genetic background and environment can be largely excluded. To test the hypothesised baseline of PMD, individuals from the "aggressive" class would be compared with individuals from the "tame" class and optionally also with an intermediate class. It is expected that animals with higher score for tameness are more susceptible to parasites (higher parasite load) than aggressive, i.e. wild animals (Fig. 2).

In order to obtain a reliable parasite prevalence in both comparative approaches, the sample for each cohort (wild/domesticated, aggressive/tame) should consist of at least 15 to 20 individuals. This sample size is considered a reasonable compromise between losing too much data from the analyses and maintaining an acceptable levels of uncertainty, which decreases rapidly with an increase in sample size from 10 to 20 individuals, but not significantly with a further increase in sample size (Jovani & Tella, 2006).

4.2. Experimental approaches to testing PMD

Furthermore, experimental approaches, i.e. experimental proto-domestication, such as the Belyaev fox experiment, will shed a much more reliable light on the matter. In an experimental approach (Fig. 2), an experimental population of wild animals, preferably the wild counterpart of already domesticated animals (e.g. pig, dog, cat, fox, mink), should first be established. Following the fox experiment of Belyaev, who started the experiment with 30 male foxes and 100 vixens (Trut, 1999), the sufficient size of the initial population would be 100 fertile females with one fertile male to about three females (this also depends on the reproductive strategy and mating system of the species). Each individual of the initial population would then be analysed and scored for parasite susceptibility - parasite load (parasite species richness and abundance), resistance (i.e. low parasite load due to active restriction of parasite proliferation by the host) and tolerance (i.e. high parasite load but the host is not diseased by the parasite). Based on the parasite susceptibility scores, the corresponding lineages would be defined (e.g. parasite resistant lineage with low parasite load, and parasite susceptible lineages: i.e. parasite-tolerant lineage with high parasite load, parasite-intolerant lineage with high parasite load; with possible additional sub-lineages). Further, selection and reproduction within the different lineages would be carried out and parasite susceptibility would be re-analysed in each generation and the frequency of domesticated traits, i.e. domestication syndrome (tameness, floppy ears, short and upturned tail, depigmentation, etc.) would be quantified. It is expected that the frequency of DS traits will increase in parasite-susceptible lineages, i.e. those with a higher parasite load.

In the alternative experimental approach with an initial population of the same size and structure, the animals would be experimentally infected with parasites (helminths and protozoa, e.g. based on parasite taxa that are otherwise common to a particular species). However, such an experimental approach would be most feasible with established laboratory animal models, e.g. mice and rats (e.g. Aebischer et al., 2018). Deliberately infected animals would then be selected for parasite susceptibility, i.e. parasite-resistant versus parasite-susceptible lineage (see above), recorded and compared for the frequency of domestication syndrome traits in the population across generations. Each subsequent generation would be experimentally re-exposed to the parasites. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise here that there is probably a threshold for infection with parasites, beyond which animals that are too susceptible (e.g. with extremely low resistance and tolerance) are only likely to become ill or die before reproducing.

Deliberate infection therefore also raises ethical concerns, as it can cause harm and suffering to the animals, which could constitute a serious breach of animal welfare standards. Another problem with such an experimental infection is the containment procedure to prevent uncontrolled spread of the parasites in the environment, although only indigenous parasites would be used. Therefore, such an experiment in vivo would be highly problematic, while in vitro assays (e.g. pluripotent stem cells or organoids, Breyner et al., 2020) would hardly provide a complete picture of PMD mechanisms due to their complexity (gut-brain/HPA axes, endocrine system, miRNA, NCC, etc., see Fig. 1).

However, it is to be expected that in both experiments the frequency of typical domestication syndrome traits increase with susceptibility or constant exposure to parasites. Indeed, the number of generations required for the detection of domestication traits is difficult to predict. In the Belyaev fox experiment, it took six generations for a clear effect of selection to emerge (Trut, 1999). However, Belyaev's initial population was selected for traits that the PMD assumes were precedingly induced by the parasites.

5. Conclusion

Parasites contribute to diversity by affecting their host at all levels and causing various phenotypic changes (morphological, behavioural, physiological). Domestication, one of the most diversification-prone evolutionary processes, and the possible mediating role of parasites in this process raise many questions and therefore open a promising area for future research, including methodological challenges, in the field of animal evolutionary biology.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

Ethics Statement

As the study did not involve humans or animals, no ethical approval was required. Permission to reproduce material from other sources was not required/relevant here.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

Adamo, S. A. (2013). Parasites: evolution’s neurobiologists. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(1), 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.073601

Aebischer, T., Matuschewski, K., & Hartmann, S. (2018). Parasite infections: from experimental models to natural systems. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 8, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00012

Antonaci, M., & Wheeler, G. N. (2022). MicroRNAs in neural crest development and neurocristopathies. Biochemical Society Transactions, 50(2), 965-974. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20210828

Bagnaresi, P., Nakabashi, M., Thomas, A. P., Reiter, R. J., & Garcia, C. R. (2012). The role of melatonin in parasite biology. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 181, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.09.010

Barribeau, S. M., Sadd, B. M., du Plessis, L., & Schmid-Hempel, P. (2014). Gene expression differences underlying genotype-by-genotype specificity in a host–parasite system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(9), 3496-3501. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318628111

Belyaev, D. K. (1969). Domestication of animals. Science Journal 5, 47-52.

Belyaev, D. K. (1979). Destabilizing selection as a factor in domestication. Journal of Heredity, 70, 301-308. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109263

Blanchet, S., Rey, O., Berthier, P., Lek, S., & Loot, G. (2009). Evidence of parasite‐mediated disruptive selection on genetic diversity in a wild fish population. Molecular Ecology, 18, 1112-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04099.x

Blecharz-Klin, K., Świerczyńska, M., Piechal, A., Wawer, A., Joniec-Maciejak, I., Pyrzanowska J, Wojnar, E., Zawistowska-Deniziak, A., Sulima-Celińska, A., Młocicki, D., & Mirowska-Guzel, D. (2022). Infection with intestinal helminth (Hymenolepis diminuta) impacts exploratory behavior and cognitive processes in rats by changing the central level of neurotransmitters. PLoS Pathogens, 18(3), e1010330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010330

Breyner, N. M., Hecht, M., Nitz, N., Rose, E., & Carvalho, J. L. (2020). In vitro models for investigation of the host-parasite interface-possible applications in acute Chagas disease. Acta tropica, 202, 105262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105262

Buck, A. H., Coakley, G., Simbari, F., McSorley, H. J., Quintana, J. F., Le Bihan, T., Kumar, S., Abreu-Goodger, C., Lear, M., Harcus, Y., Ceroni, A., Babayan, S. A., Blaxter, M., Ivens, A., & Maizels, R. M. (2014). Exosomes secreted by nematode parasites transfer small RNAs to mammalian cells and modulate innate immunity. Nature communications, 5(1), 5488. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6488

Cheeseman, K., & Weitzman, J. B. (2015). Host–parasite interactions: an intimate epigenetic relationship. Cellular Microbiology, 17(8), 1121-1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12471

Chowdhury, S., Sais, D., Donnelly, S., & Tran, N. (2024). The knowns and unknowns of helminth–host mirna cross-kingdom communication. Trends in Parasitology, 40(2), 176-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2023.12.003

Coakley, G., Buck, A. H., & Maizels, R. M. (2016). Host parasite communications—Messages from helminths for the immune system: Parasite communication and cell-cell interactions. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 208(1), 33-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.06.003

Del Giudice, M. (2019). Invisible designers: brain evolution through the lens of parasite manipulation. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 94, 249-282. https://doi.org/10.1086/705038

Duffy, M. A., Brassil, C. E., Hall, S. R., Tessier, A. J., Cáceres, C. E., & Conner, J. K. (2008). Parasite-mediated disruptive selection in a natural Daphnia population. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 8(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-80

Feldmeyer, B., Mazur, J., Beros, S., Lerp, H., Binder, H., & Foitzik, S. (2016). Gene expression patterns underlying parasite‐induced alterations in host behaviour and life history. Molecular Ecology, 25(2), 648-660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13498

Fitz-James, M. H., & Cavalli, G. (2022). Molecular mechanisms of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nature Reviews Genetics, 23(6), 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-021-00438-5

Floris, I., Kraft, J. D., & Altosaar, I. (2016). Roles of microRNA across prenatal and postnatal periods. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(12), 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17121994

Frick, A., Björkstrand, J., Lubberink, M., Eriksson, A., Fredrikson, M., & Åhs, F. (2022). Dopamine and fear memory formation in the human amygdala. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(3), 1704-1711. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01400-x

Gopinath, A., Mackie, P. M., Phan, L. T., Mirabel, R., Smith, A. R., Miller, E., Franks, S., Syed, O., Riaz, T., Law, B. K., Urs, N., & Khoshbouei, H. (2023). Who Knew? Dopamine Transporter Activity Is Critical in Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. Cells, 12(2), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12020269

Gopko, M. V., & Mikheev, V. N. (2019). Parasitic manipulations of the host phenotype: effects in internal and external environments. Biology Bulletin Reviews, 9(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079086419010018

Gurtan, A. M., & Sharp, P. A. (2013). The role of miRNAs in regulating gene expression networks. Journal of molecular biology, 425(19), 3582-3600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2013.03.007

Hasik, A. Z., Ilvonen, J. J., Gobbin, T. P., Suhonen, J., Beaulieu, J. M., Poulin, R., & Siepielski, A. M. (2025). Parasitism as a driver of host diversification. Nature Reviews Biodiversity 1, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00045-w

He, X., & Pan, W. (2022). Host–parasite interactions mediated by cross-species microRNAs. Trends in parasitology, 38(6), 478-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2022.02.011

Helluy, S., & Thomas, F. (2003). Effects of Microphallus papillorobustus (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda) on serotonergic immunoreactivity and neuronal architecture in the brain of Gammarus insensibilis (Crustacea: Amphipoda). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 270(1515), 563-568. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2264

Hernandez-Caballero, I., Garcia-Longoria, L., Gomez-Mestre, I., & Marzal, A. (2022). The adaptive host manipulation hypothesis: parasites modify the behaviour, morphology, and physiology of amphibians. Diversity, 14(9), 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14090739

Hughes, D. P., & Libersat, F. (2019). Parasite manipulation of host behavior. Current Biology, 29, R45-R47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.001

Jezkova, T., & Wiens, J. J. (2017). What explains patterns of diversification and richness among animal phyla?. The American Naturalist, 189(3), 201-212. https://doi.org/10.1086/690194

Jovani, R., & Tella, J. L. (2006). Parasite prevalence and sample size: misconceptions and solutions. Trends in parasitology, 22(5), 214-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.011

Judice, C. C., Bourgard, C., Kayano, A. C., Albrecht, L., & Costa, F. T. (2016). MicroRNAs in the host-apicomplexan parasites interactions: a review of immunopathological aspects. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2016.00005

Karaer, M. C., Čebulj-Kadunc, N., & Snoj, T. (2023). Stress in wildlife: comparison of the stress response among domestic, captive, and free-ranging animals. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10, 1167016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1167016

Kaushik, M., Lamberton, P. H., & Webster, J. P. (2012). The role of parasites and pathogens in influencing generalised anxiety and predation-related fear in the mammalian central nervous system. Hormones and behavior, 62(3), 191-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.002

Love, A. C., & Wagner, G. P. (2022). Co-option of stress mechanisms in the origin of evolutionary novelties. Evolution, 76(3), 394-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14421

Matthews, S. G., & Phillips, D. I. (2012). Transgenerational inheritance of stress pathology. Experimental Neurology, 233, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.01.009

Monsoro-Burq, A. H. (2015). PAX transcription factors in neural crest development. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 44, 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.09.015

Morgan, H. D., Sutherland, H. G., Martin, D. I., & Whitelaw, E. (1999). Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nature genetics, 23(3), 314-318. https://doi.org/10.1038/15490

Nadler, L. E., Adamo, S. A., Hawley, D. M., & Binning, S. A. (2023). Mechanisms and consequences of infection‐induced phenotypes. Functional Ecology, 37(4), 796-800. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14309

Nuismer, S. L., & Otto, S. P. (2005). Host–parasite interactions and the evolution of gene expression. PLoS Biology, 3(7), e203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030203

O’Dwyer, K., Dargent, F., Forbes, M. R., & Koprivnikar, J. (2020). Parasite infection leads to widespread glucocorticoid hormone increases in vertebrate hosts: A meta‐analysis. Journal of animal ecology, 89(2), 519-529. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13123

Oleinic, R., Posedi, J., Beck, R., Šprem, N., Škorput, D., Pokorny, B., Škorjanc, D., Prevolnik Povše, M., & Skok, J. (2024). Testing the ‘parasite-mediated domestication’hypothesis: a comparative approach to the wild boar and domestic pig as model species. PeerJ, 12, e18463. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.18463

Park, Y. (2017). MicroRNA exocytosis by vesicle fusion in neuroendocrine cells. Frontiers in endocrinology, 8, 355. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00355

Pasquinelli, A. E. (2012). MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13, 271-282. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3162

Paul, S., Ruiz-Manriquez, L. M., Serrano-Cano, F. I., Estrada-Meza, C., Solorio-Diaz, K. A., & Srivastava, A. (2020). Human microRNAs in host–parasite interaction: a review. 3 Biotech, 10, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-020-02498-6

Poulin, R. (1994). The evolution of parasite manipulation of host behaviour: a theoretical analysis. Parasitology, 109(S1), S109-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000085127

Poulin, R., & Thomas, F. (1999). Phenotypic Variability Induced by Parasites: Extent and Evolutionary Implications. Parasitology Today, 15, 28-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(98)01357-X

Poulin, R. (2010). Parasite manipulation of host behavior: an update and frequently asked questions. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 41, 151-186). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3454(10)41005-0

Poulin, R. (2013). Parasite manipulation of host personality and behavioural syndromes. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(1), 18-26. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.073353

Rakyan, V. K., Chong, S., Champ, M. E., Cuthbert, P. C., Morgan, H. D., Luu, K. V., & Whitelaw, E. (2003). Transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic states at the murine Axin Fu allele occurs after maternal and paternal transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(5), 2538-2543. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0436776100

Rojas-Pirela, M., Andrade-Alviárez, D., Quiñones, W., Rojas, M. V., Castillo, C., Liempi, A., Medina, L., Guerrero-Muñoz, J., Fernández-Moya, A., Ortega, Y. A., Araneda, S., Maya, J. D., & Kemmerling, U. (2023). microRNAs: Critical Players during Helminth Infections. Microorganisms, 11(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11010061

Ruff, J. S., Nelson, A. C., Kubinak, J. L., & Potts, W. K. (2012). MHC signaling during social communication. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 738, 290-313. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1680-7_17

Sandland, G. J., & Goater, C. P. (2001). Parasite-induced variation in host morphology: brain-encysting trematodes in fathead minnows. Journal of Parasitology, 87(2), 267-272. https://doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0267:PIVIHM]2.0.CO;2

Sharma, A. (2014). Novel transcriptome data analysis implicates circulating microRNAs in epigenetic inheritance in mammals. Gene, 538(2), 366-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2014.01.051

Shaw, T., Barr, F. G., & Üren, A. (2024). The PAX Genes: Roles in Development, Cancer, and Other Diseases. Cancers, 16, 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16051022

Skinner, M. K. (2014). Environmental stress and epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. BMC Medicine 12, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0153-y

Skok, J. (2023). The parasite-mediated domestication hypothesis. Agricultura Scientia, 20, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.18690/agricsci.20.1.1

Thomas, F., Poulin, R., & Brodeur, J. (2010). Host manipulation by parasites: a multidimensional phenomenon. Oikos, 119(8), 1217-1223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.18077.x

Trapezov, O. V. (1987). Селекционное преобразование оборонительной реакции на человека у американской норки. Genetika, 23(6), p.1120.

Trut, L. N. (1999). Early Canid Domestication: The Farm-Fox Experiment: Foxes bred for tamability in a 40-year experiment exhibit remarkable transformations that suggest an interplay between behavioral genetics and development. American Scientist, 87(2), 160-169.

Trut, L. N., & Kharlamova, A. V. (2020). Domestication as a process generating phenotypic diversity. In Phenotypic Switching (pp. 511-526). Academic Press.

van Otterdijk, S. D., & Michels, K. B. (2016). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals: how good is the evidence?. The FASEB Journal 30(7), 2457-2465. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201500083

Wang, S. J., Sharkey, K. A., & McKay, D. M. (2018). Modulation of the immune response by helminths: a role for serotonin?. Bioscience Reports, 38, BSR20180027. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20180027

Weiner, A. M. (2018). MicroRNAs and the neural crest: from induction to differentiation. Mechanisms of development, 154, 98-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mod.2018.05.009

Wijayawardena, B. K., Minchella, D. J., & DeWoody, J. A. (2016). The influence of trematode parasite burden on gene expression in a mammalian host. BMC genomics, 17(1), 600. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2950-5

Wilkins, A. S., Wrangham, R. W., & Fitch, W. T. (2014). The “domestication syndrome” in mammals: a unified explanation based on neural crest cell behavior and genetics. Genetics, 197, 795-808. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.114.165423

Xu, L., Yang, B. F., & Ai, J. (2013). MicroRNA transport: a new way in cell communication. Journal of cellular physiology, 228(8), 1713-1719. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24344

Yao, Q., Chen, Y., & Zhou, X. (2019). The roles of microRNAs in epigenetic regulation. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 51, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.01.024

Zhang, X., Flick, K., Rizzo, M., Pignatelli, M., & Tonegawa, S. (2025). Dopamine induces fear extinction by activating the reward-responding amygdala neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(18), e2501331122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2501331122

Zeng, Y., & Wiens, J. J. (2021). Species interactions have predictable impacts on diversification. Ecology Letters 24(2), 239-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13635

Zheng, Y., Cai, X., & Bradley, J. E. (2013). microRNAs in parasites and parasite infection. RNA biology, 10(3), 371-379. https://doi.org/10.4161/rna.23716