Transforming Cancer Care by Transitioning from Traditional Chemotherapy to Advanced CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy

© 2026 Bio Communications

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Abstract

The treatment for cancer has undergone a paradigm shift in recent years due to the introduction of cellular-based targeted therapies and immunotherapy, particularly Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T Cell Therapy. This narrative review examines the biology of how CARs function, along with the advances made in the development of CAR construct design over the last 3 decades. These advances include the addition of co-stimulatory signals such as CD28 and 4-1BB in the new generation CARs that improved T Cell proliferation and longevity. There have been multiple different Cancer types that have demonstrated a high degree of effectiveness using CAR-T Cell therapy, and the US FDA has approved the use of CAR-T Cell therapies for treatment of certain hematological malignancies, specifically B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. However, there remains a significant limitation for the use of CAR-T Cell therapies for solid tumor therapies. Three major limitations preventing CAR-T Cell therapies from being used as an effective treatment for solid tumors include the existence of an immune suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), the physical barriers preventing T Cells from migrating to tumor sites, as well as tumor antigen heterogeneity preventing treatment efficacy. This review discusses potential emerging modalities for overcoming some of these limitations, including the development of "armored" CAR-T Cells, the use of multi-antigen targeting strategies to prevent antigen escape, and the development of combinatorial approaches to modulate the TME. Lastly, this review discusses future opportunities in the development of CAR-T Cell therapies, including the development of "off-the-shelf" allogeneic CAR-T Cells, in vivo gene delivery systems to create CAR-T Cells, and gene editing via CRISPR/Cas9 systems to increase the safety profile of CAR-T Cells and expand their therapeutic application beyond blood cancers.

Keywords:

Immunotherapy, Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy, Hematological Malignancies, Solid Tumors, Tumor Microenvironment

1. Introduction

Cancer treatment has changed greatly and now relies less on traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, which targets rapidly growing cells by targeting many of them indiscriminately. Now, however, modern treatments seek to use the power of the body's own immune system to treat cancer, such as the use of immunotherapy (Sriwastava et al., 2024). One such type of innovative and effective immunotherapy is known as “chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy” (CAR-T) (Sriwastava et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). This type of therapy allows T-cells, through genetic engineering, to have both a synthetic receptor for an antigen and also have potent T-cell activation. With this dual-action receptor, T-cells can specifically find and destroy cancer cells that are expressing a certain antigen, thus leading to more personalized and effective options in treatment (Sahlolbei et al., 2024).

The purpose of this narrative review is to critique the success of CAR-T cell therapy in hematologic malignancies, identify barriers to success for CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors, and to propose potential strategies for overcoming these obstacles (Dagar et al., 2023; Poojary et al., 2023; Sriwastava et al., 2024). Additionally, there will be a specific focus on the mechanism of action, as well as the optimized design and performance of CARs; each generation of CAR design and the clinical influence resulting from that design (Ercilla-Rodríguez et al., 2024). A comparison of the evolutionary enhancements in each consecutive generation of CARs will be presented, specifically with regard to how the added components of co-stimulatory domains and additional genetic modifications are being incorporated into the evolving CAR technology, ultimately improving their effectiveness while improving their viability within the harsh tumor microenvironments (Zafar et al., 2024). Additionally, this review will describe the many limitations that currently hinder the application of CAR-T cell therapy to solid tumors, including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, the lack of unique tumor-specific antigens, and the problems associated with trafficking of CAR-T cells, and to evaluate innovative adjunct therapies and gene editing technologies that may improve the quality and quantity of effective therapeutic CAR-T cells (Ali & DiPersio, 2024; Zhu et al., 2025). Additionally, a discussion of the complexities associated with the manufacturing process for CAR-T cells, including the manufacturing process for apheresis to ex vivo programming and expansion of CAR-T cells for wider application of this new therapy will be included(El-Daly & Hussein, 2019). While recent literature has extensively documented clinical trial endpoints or isolated engineering strategies, there remains a need to holistically examine how the molecular evolution of CAR architecture directly correlates with clinical efficacy in solid tumors. Unlike previous reviews, this article critically evaluates the interplay between next-generation CAR constructs (such as armored and logic-gated CARs) and the specific physiological barriers of the tumor microenvironment (TME). We aim to provide a roadmap that transitions from a historical overview of hematological successes to a prospective analysis of how combinatorial engineering can overcome the stagnation currently observed in solid tumor treatments.

2. The Dawn of Cancer Immunotherapy

The discovery of tumor immunology and the complex interactions between cancer cells and the immune system of the host has resulted in an important shift from non-specific treatment options to targeted immunotherapy types (Poojary et al., 2023). This knowledge has allowed researchers and practitioners to create therapies like immune checkpoint blockade and adoptive T-cell therapy, which are aimed at returning or enhancing a patient’s anti-tumor immunity. Among the developed types of therapies, CAR-T cell therapy has gained a great deal of attention and success, particularly in the area of hematologic malignancies. As a result of the success of a number of CAR-T cell therapies, the FDA has approved them (Roselli et al., 2021). Even though there have been advancements in CAR-T cell therapies and there continue to be studies to create strategies to increase CAR-T cell persistence, to have CAR-T cells better target solid tumors, and to reduce the impact of immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment, significant barriers exist to enabling CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors (Chang et al., 2024; Du et al., 2025).

Engineering CAR-T cells to overexpress specific cytokines, which function as biological messengers that coordinate/regulate the immune system (and therefore enhance CAR-T cell function), is another avenue to enhance CAR-T cell therapy. Targeting two proteins with CARs improves efficacy when dealing with heterogeneity, as patients' tumors contain multiple antigens to which CARs can bind. Armored CAR-T cells are those that are engineered with additional antitumor "armoring" receptors that enable these CAR-T cells to withstand the effects of immunosuppression on the part of the tumor microenvironment (Tufail et al., 2025). In parallel, logic-gated CAR-T cells represent another early example of new strategies to optimize the efficiency of CAR-T cell therapy while minimizing the possibility of undesirable side effects. Improved techniques for delivering CAR-T cells directly to tumors will also be part of the ongoing improvement of CAR-T cell therapy (Chen et al., 2024).

Synthetic biology technologies have facilitated the development of CARs, which have increased safety features (suicide genes and switchable signaling components) (Huang et al., 2023), and greater options for manipulating T-cell activity. To extend the application of CAR-T cell therapy to a wider range of tumors (beyond hematologic malignancies) (Uslu & June, 2024), continued progression in the engineering of CARs and related strategies will continue to be necessary. Innovations in CAR design that build upon the advances made in earlier generations of CAR products will need to be made in order to allow for maintenance of CAR-T cell functionality within the hostile environments associated with solid tumors and to prevent antigen escape (Dagar et al., 2023; Sahlolbei et al., 2024).

The early CAR designs relied heavily on a basic understanding of how to recognize antigens and to activate T-cells. The sophistication of modern CAR designs reflects this increased understanding of immune interactions of the CAR-T cells. Modern CAR designs frequently contain additional co-stimulatory domains and contain expression cassettes for cytokines as a means of enhancing T-cell expansion and maintaining activity against tumors that otherwise would be difficult to target (Devaraji & Varghese Cheriyan, 2025). These enhancements in CAR designs are intended to reduce T-cell exhaustion and the immunosuppressive characteristics of solid tumors, both of which hinder the ability of CAR-T therapies that use classic CAR structures to achieve their optimal potential for efficacy (Chen et al., 2024). There are several options for advanced CAR designs and additional mechanisms, including the use of tandem CARs or inducible CARs, that are being investigated to address antigen loss problems and to improve specificity for targeting heterogeneous tumors (Andreou et al., 2025).

Co-expression of co-stimulatory ligands or cytokines to create armored CAR-T cells has shown to provide significant advantages in terms of enhanced progression toward regression and retention of tumors observed in preclinical studies, resulting in improved potential for generating strong immune responses against tumors (Luo & Zhang, 2024). Further developments in advanced CAR designs, such as developing safety switches for CAR-T cells (inducible caspase 9 [iCasp9]) will provide better control over the CAR-T cell activity, through precise destruction of CAR-T cells with severe toxicities (Andreou et al., 2025). These novel CAR designs will mitigate some of the major obstacles to the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors and to reduce the risk of nonspecific toxicity.

3. CAR-T Cells: Mechanism and Design

CAR-T cell therapy is a novel and promising form of immunotherapy for treating cancers, especially in hematological malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma, due to their unique characteristics and ability to target cancer cells. The initial CARs were developed with one main goal: to use genetically modified T-cells for killing cancer cells in vivo. Today CARs are being developed with many different goals, including improving the ability of T-cells to attack solid tumors, enhancing the ability of the immune system to destroy infected cells or tumour cells that have developed resistance to chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and creating CARs capable of producing cytokines that stimulate other immune cells to attack cancer cells. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, which causes systemic cytotoxicity affecting rapidly dividing healthy tissues, CAR-T cell therapy offers precise target specificity. However, this specificity is accompanied by unique, potentially life-threatening immunotoxicities, most notably Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS). While CAR-T therapy avoids the chronic cumulative organ damage often seen with chemotherapy (e.g., anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity), the acute management of systemic inflammation remains a significant clinical challenge. For these reasons, CAR-T cells have many potential uses in the treatment of cancer.

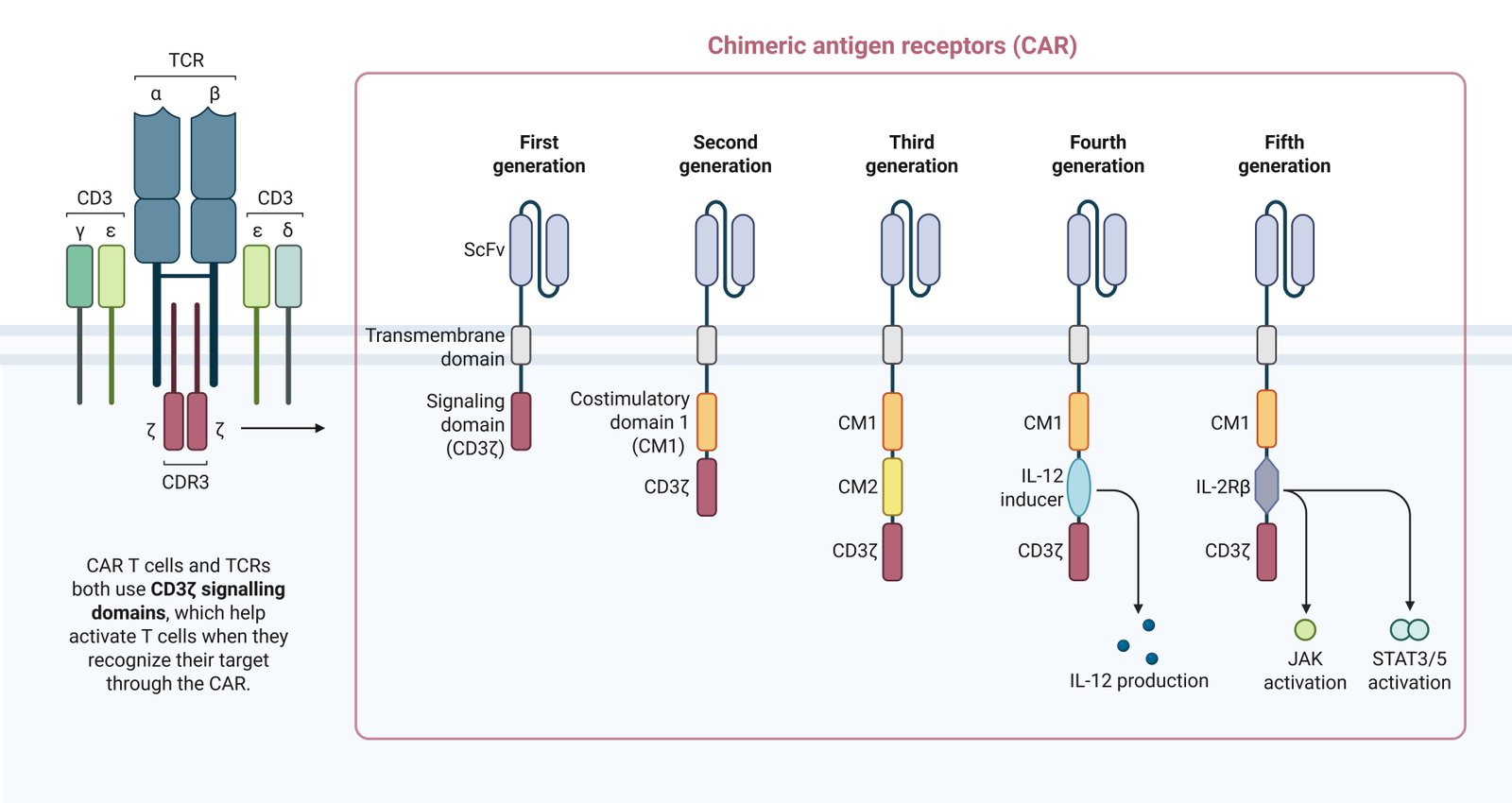

3.1. Structural Evolution and Signaling Kinetics

A fundamental CAR construct consists of an extracellular antigen-binding domain (scFv), a hinge and transmembrane region, and intracellular signaling domains (Fig. 1). The evolution of CAR design is defined by the progressive optimization of intracellular signaling to balance cytotoxicity with persistence. First-generation CARs, containing only the CD3ζ signaling domain, failed clinically due to insufficient T-cell proliferation and rapid anergy. The incorporation of co-stimulatory domains (CD28 or 4-1BB) in second-generation CARs proved critical for survival and expansion.

A critical distinction lies in the metabolic programming induced by these domains. CD28-based CARs (e.g., axicabtagene ciloleucel) drive a potent, rapid effector response utilizing aerobic glycolysis, often at the cost of faster exhaustion. In contrast, 4-1BB-based CARs (e.g., tisagenlecleucel) promote mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism, favoring a central memory phenotype and prolonged persistence. Third-generation CARs combine multiple co-stimulatory domains (e.g., CD28 and 4-1BB) to leverage both cytolytic potency and longevity; however, clinical data suggests that simply adding domains does not consistently yield superior efficacy over optimized second-generation constructs (Table 1). Current research has shifted toward fine-tuning these signaling motifs or exploring novel domains like ICOS and OX40 to prevent tonic signaling and exhaustion.

| Generation | Structural Composition | Signaling Signals | Primary Functional Goal | Key Advantages/Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | scFv + CD3ζ | Signal 1 (Activation) | Proof-of-Concept |

Adv: Established MHC-independence. Dis: No persistence; rapid anergy/apoptosis. |

| Second | scFv + CD28/4-1BB + CD3ζ | Signal 1 + Signal 2 (Co-stimulation) | Clinical Efficacy & Persistence |

Adv: Robust expansion; basis of all FDA approvals. Dis: Susceptible to exhaustion; limited in solid tumors. |

| Third | scFv + CD28 + 4-1BB + CD3ζ | Signal 1 + Dual Signal 2 | Hybrid Kinetics |

Adv: Theoretical blend of speed and durability. Dis: Risk of hyper-activation; complex manufacturing. |

| Fourth (TRUCKs) | Gen 2 CAR + Inducible Cytokine (IL-12, IL-18) | Signal 1 + 2 + Paracrine Modulation | TME Remodeling (Solid Tumors) |

Adv: Recruits innate immunity; fights suppression. Dis: Risk of systemic cytokine toxicity (e.g., IL-12). |

| Fifth | Gen 2 CAR + Cytokine Receptor Domain (IL-2Rβ) | Signal 1 + 2 + JAK-STAT (Signal 3) | Autocrine Persistence |

Adv: Antigen-dependent cytokine signaling; memory formation. Dis: Early development; complex regulation needed. |

4. Clinical Success in Hematological Malignancies

The use of CAR-T cells for treating many forms of hematological malignancies has shown remarkable effectiveness, resulting in prolonged remissions for patients who had otherwise failed to respond to therapies (Ramos et al., 2016). The introduction of CAR-T cell therapy has significantly changed the landscape for cancer treatment in many different cancer types and is particularly relevant to the management of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma (Table 2) (Kaur et al., 2025).

| Target | Therapy (Trade Name) | Indication | Co-stim | Pivotal Trial | Efficacy Highlights | Grade ≥3 Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) | Ped. ALL; DLBCL; FL | 4-1BB | ELIANA (ALL); JULIET (DLBCL) | ALL: 82% ORR; DLBCL: 52% ORR, 38% CR. 5-year durable remissions seen in ALL. | CRS: 49% (ALL); ICANS: 21% (ALL). |

| CD19 | Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) | LBCL (2L+); FL | CD28 | ZUMA-7 (LBCL 2L) | LBCL: Superior EFS vs ASCT. 83% ORR, 65% CR. Potent rapid expansion. | CRS: ~11%; ICANS: ~31%. High toxicity requires inpatient care. |

| CD19 | Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) | MCL; Adult ALL | CD28 | ZUMA-2 (MCL); ZUMA-3 (ALL) | MCL: 93% ORR, 67% CR. ALL: 71% CR/CRi. Highly effective in refractory MCL. | CRS: 18% (MCL), 26% (ALL); ICANS: 37% (MCL), 35% (ALL). |

| CD19 | Lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi) | LBCL; CLL; FL; MCL | 4-1BB | TRANSCEND | LBCL: 73% ORR, 53% CR. CLL: 45% CR. Consistent potency via 1:1 CD4:CD8 ratio. | CRS: 3.2%; ICANS: 10%. Best-in-class safety profile. |

| CD19 | Obecabtagene autoleucel (Aucatzyl) | Adult ALL | 4-1BB | FELIX | ALL: 63% Overall CR/CRi. Fast off-rate reduces exhaustion. | CRS: 3%; ICANS: 7%. Significantly lower toxicity than Tecartus. |

| BCMA | Idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma) | MM (2L+) | 4-1BB | KarMMa-3 | Median PFS 13.3 mo vs 4.4 mo (SOC). First BCMA approval. | CRS: 5-7%; ICANS: 4%. |

| BCMA | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Carvykti) | MM (1L+) | 4-1BB | CARTITUDE-4 | Reduced progression risk by 74%. Bi-epitopic binding for high avidity. | CRS: 4-5%; ICANS: Low. Boxed Warning: Delayed Parkinsonism/Enterocolitis. |

4.1. B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL)

High efficacy rates (greater than 80% complete remissions) for patients under the age of 18 with relapsed/refractory B-ALL treated with CD19-targeted CAR-T cell products have resulted in multiple FDA product approvals for the use of these products in this patient population. Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) was shown to produce durable remissions in a cohort of patients with chronic lymphoblastic leukaemia (CLL) who had previously been treated with multiple regimens; Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (Yescarta) and Brexucabtagene Autoleucel (brexu-cel) have produced similar results in the treatment of aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The continued development of CD19-targeted CAR-T cells has been enhanced through the success of these products (D. Sun et al., 2024; R. Sun et al., 2024), with the target of these therapies being CD19, a component of an immunological response to B-ALL and B-cell lymphomas, and a protein found on almost all B lymphocytes (including malignant B lymphocytes). CD19-targeted therapies have proven to be an integral component of immunotherapy for patients with B-ALL and B-cell lymphoma.

4.2. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has responded to CAR-T cell therapy with unprecedented success, as indicated by response rates and durable remissions published in studies (Liang, 2021). Recent FDA approvals of CD19-directed CAR-T cell products provided new treatment modalities for individuals who have exhausted current therapies (Cuenca et al., 2022). The ZUMNA-1 and JULIET clinical trials substantiate the efficacy and safety profiles of axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel among this difficult-to-treat population (Schwerdtfeger et al., 2021). Follow-up of patients participating in these clinical trials has consistently shown responding to CAR-T cell therapy with greater than an 80% objective response rate and approximately 50% complete response rates, establishing CAR-T cell therapy as the standard of care for relapsed/refractory DLBCL (Kosti et al., 2018). Standard treatment prior to the arrival of CAR-T cell therapy was chemotherapy such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone); with the addition of monoclonal antibody such as rituximab. There is now evidence that CAR-T cell therapy can be used to treat patients who have relapsed/refractory disease after receiving one or more rounds of conventional therapy, and provides superior outcomes when compared to conventional therapies (Jutzi et al., 2025).

4.3. Multiple Myeloma and Other Blood Cancers

Through the development of CAR-T cell treatments for B-cell malignancies, research has now moved into targeting other forms of hematological cancer. Multiple Myeloma is being effectively treated with B-cell maturation antigen targeted CAR-T cells, as they have shown encouraging results in clinical trials (Sahlolbei et al., 2024). For example, the FDA has approved the CAR-T cell therapy called idecabtagene vicleucel for patients who are suffering from relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and have had significant success rates (Dagar et al., 2023). Furthermore, another product called ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) that targets the B-cell maturation antigen, has also produced substantial long-term success in patients who have been heavily pre-treated for multiple myeloma, thereby increasing the potential treatment options for this difficult-to-treat disease. Therefore, this research indicates that many hematological malignancies will benefit greatly from the advancements in CAR-T cell technology through its application across a variety of hematological malignancies such as mantle cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma, where CD19 therapies are currently underway (Zhang et al., 2022). The approval of CAR-T cell therapy by the FDA has dramatically changed the way in which multiple hematological malignancies are treated, with overall response rates among some hematological malignancies, including Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Large B Cell Lymphoma, Follicular Lymphoma, Mantle Cell Lymphoma, Marginal Zone Lymphoma, and Multiple Myeloma reaching as high as 97% (Andreou et al., 2025; Satapathy et al., 2024). Clearly, the progress made to date regarding CAR-T cell therapy demonstrates that it has the potential to dramatically change the landscape for patients with hematological malignancies who have run out of treatment options (Zhong & Liu, 2024).

4.4. Clinical Limitations

Despite high initial response rates in hematological malignancies, long-term efficacy is tempered by toxicity and relapse mechanisms. The two most significant adverse events are CRS and ICANS, driven by the rapid systemic release of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IFN-γ) following CAR-T expansion (Brudno & Kochenderfer, 2024; Schroeder et al., 2024). While generally manageable with tocilizumab and corticosteroids, high-grade CRS remains a barrier to outpatient administration, with grade ≥3 CRS occurring in approximately 20% of older patients (Schroeder et al., 2024).

Furthermore, relapse occurs in approximately 30-50% of patients with B-ALL and DLBCL. This is primarily driven by two mechanisms: (1) Antigen Escape, where the tumor downregulates the target protein (e.g., CD19-negative relapse), and (2) CAR-T Exhaustion, where the therapeutic cells persist but lose functional capacity due to chronic antigen exposure (Ruella et al., 2023). Long-term follow-up from the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial indicates that while axicabtagene ciloleucel offers curative potential with a 5-year overall survival rate of 42.6%, identifying biomarkers to predict resistance remains an urgent clinical priority (Neelapu et al., 2023).

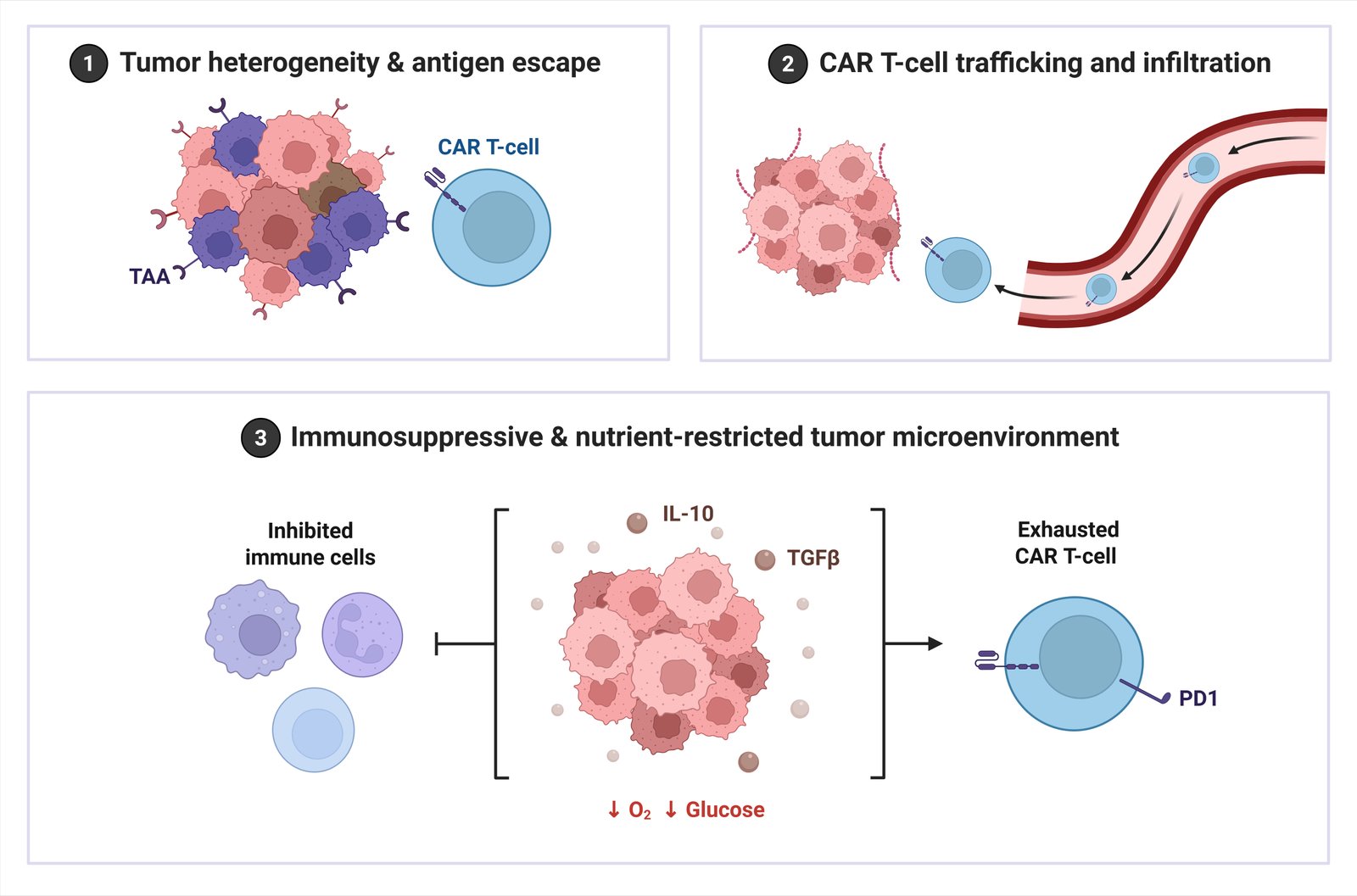

5. Challenges in Solid Tumor Treatment

While hematological successes are driven by high target accessibility, clinical trials in solid tumors reveal a hierarchy of barriers. The primary reason for trial failure is not merely antigen recognition, but inefficient trafficking and infiltration, where CAR-T cells fail to penetrate the desmoplastic stroma. Even when infiltration occurs, the immunosuppressive TME, characterized by hypoxia and metabolic exhaustion, rapidly renders T-cells dysfunctional (Fig. 2). Antigen heterogeneity and escape represent secondary mechanisms of resistance that become relevant only after successful infiltration and initial killing are achieved.

5.1. Tumor Microenvironment Barriers

The chemical barriers in the tumor microenvironment have severely limited the progress and success of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. By assessing the tumor physiological environment, the various methods by which the tumor microenvironment hinders the infiltration of CAR-T cells can begin to be identified. Many solid tumors possess an abundant amount of suppressive immune factors such as a challenging extracellular matrix, limited amounts of oxygen, as well as a high density of both; thus each of these three characteristics work together to create a synergistic impact on T-cell suppression which hinders T-cell proliferation and activation and ultimately leads to the ineffectiveness of CAR-T cells at infiltrating and causing lasting effects on solid tumors. In addition, CAR-T cells competition with other cells within the tumor environment, primarily due to nutrient availability, acts to impair CAR-T cell function and proliferation. The regulatory T-cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and tumor-associated macrophages create an immunosuppressive tumor environment by acting as competing cells for nutrients and activating regulatory T-cells for immunosuppressive actions on other immune cells. Moreover, CAR-T cells experience T-cell exhaustion after repeated stimulation through their antigen receptors, which is typically driven by a chronic exposure to the antigen. Chronic stimulation of the T-cell receptor through CAR-T cell therapy, in conjunction with chronic exposure to the tumor antigens, leads to exhaustion of the CAR-T cells due to the up-regulation of both the PD-1 and LAG3 coinhibitory receptors. This results in a failure of CAR-T cells to exert cytotoxicity upon the tumor cells. Tumor-associated macrophages express lipid-enriched metabolic phenotypes that are distinct from those of resting macrophages. Various metabolic alterations exist within the tumor microenvironment due to the unique metabolic phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages and eventually impair T-cell-mediated anti-tumor activity and provide supportive networking. Other physical barriers include a dense network of ECM and an abnormal vascularity, which prevent T-cells from adequately trafficking to and utilizing straight access to the inner tumor microenvironment. Ultimately, when CAR-T cells eventually cross the endothelial barrier, survival rates are at a low percentage (approximately 1% to 2%) of the actual number of CAR-T cells infused into the blood supply, thereby markedly decreasing the potency and ability of the CAR-T cells to kill (Liu et al., 2024). A dense tumor stroma can act as a significant physical barrier to CAR-T cell mobility and access to malignant cells (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2020). However, the combination of physical barriers and cellular barriers in the solid tumor environment, (including an abundance of soluble immunosuppressive factors and altered cytokine and chemokine expression), create significant obstacles for CAR-T cell function and viability.

5.2. Antigen Heterogeneity and Loss

A critical limitation in the management of solid tumors, and in particular the development of CAR-T cells, is tumour heterogeneity and antigen escape. The absence of an associated phenotype is one of the key differences between solid tumours and leukaemias or lymphomas. While leukemias and lymphomas often have identical immunophenotypic markers such as CD19 or BCMA; solid tumours usually do not have a common marker that can be recognised by the CAR-T cell therapy. The diversity in antigen expression patterns within tumours leads to the inability to completely remove all tumour cells; therefore, there is the potential for the growth of antigen-negative tumour clones, which ultimately leads to the development of treatment-resistant disease (Anderson et al., 2021). Additionally, the selective pressure imposed by CAR-T cell treatment may create a situation where tumour cells lose or downregulate the targeted antigen, as was shown in children with CD19+ B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia who successfully responded to CAR-T cell therapy (Qu et al., 2022). There is a wide variety of mechanisms through which antigen escape can occur, including but not limited to, epigenetic alterations, mutations in DNA, and alternative splicing events that create aberrant proteins that either fundamentally alter the function of the tumour cell or render it unrecognisable by the CAR-T cells.

5.3. T-Cell Trafficking and Persistence

The success of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors is contingent upon the ability of engineered T cells ability to migrate to the tumor site and remain there long enough for cytotoxic activity to occur (Sterner & Sterner, 2021). Important reasons that limit CAR-T cell therapy's success against solid tumors include how the CAR-T cells navigate successfully from the bloodstream to the tumor core and how they can sustain their activity in a hostile tumor microenvironment (Jaing et al., 2025). Biological factors that impede CAR-T cell therapy effectiveness include the inability of the CAR-T cells to extravasate correctly from the bloodstream, as well as obstacles encountered during the CAR-T cell migration through the dense extracellular matrix, leading to poor intratumoral CAR-T cell distribution (Guzman et al., 2023; Nasiri et al., 2023). Furthermore, limited CAR-T cell homing and infiltration into tumor cells (especially in avascular regions) contribute to the decreased therapeutic effect of CAR-T cell therapies compared to other therapies (Chen & Zhou, 2025).

6. Strategies to Overcome Limitations

To address these multifactorial barriers, researchers are exploring innovative strategies, including engineering CAR-T cells with enhanced trafficking capabilities and resistance to immunosuppression.

6.1. Enhancing CAR-T Cell Persistence and Efficacy

Novel Strategies are focused on optimizing CAR constructs to maximize T-cell proliferation, persistence, and effector (tumor killing) functions while they are exposed to a hostile tumor microenvironment (Maalej et al., 2023). With regard to that goal, those efforts include the use of co-stimulatory domains to enhance T-cell survival and cytokine secretion, engineering CARs to prevent CAR-T cell exhaustion and anergy (Li et al., 2018), and genetically modifying CAR-T cells ability to secrete dominant-negative receptors and/or immunomodulatory cytokines to improve the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells while overcoming immunosuppression (Leyfman, 2018). To subsequently enhance the CAR-T cells recruitment and continued activation at the tumor microenvironment, adoptive transfer strategies are employing localization of inducible cytokine secretion and/or localized chemokine expression systems (Dagar et al., 2023). Another potential area for improvement currently being studied is the engineering of CAR-T cells to express enhanced chemokine receptor expression, allowing for improved CAR-T cell homing and hence infiltration of solid tumors (Yu et al., 2024). These approaches may eventually help to ameliorate some of the inherent limitation of CAR-T cells from having a high accumulation in the lungs and secondary lymphoid tissues initially, followed by poor infiltration of CAR-T cells into the tumor cells (Nie, 2025).

To counteract TME suppression, "armored" CARs are engineered to secrete cytokines (e.g., IL-12, IL-18) to reshape the immune microenvironment. In preclinical murine models, these constructs have demonstrated the ability to recruit endogenous immune cells and sustain cytotoxicity. However, clinical translation remains in the early phases due to safety concerns; for instance, trials investigating constitutive IL-12 secretion have highlighted a narrow therapeutic window, necessitating the development of strict inducible control systems (e.g., Tet-On systems) which are currently undergoing safety validation in humans (Lu et al., 2024).

6.2. Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment

Given the complex ways that tumors are able to suppress immune functions, modifying the TME at the same time as CAR-T cells are being developed is critical to enhancing the effectiveness of CAR-T cells. There are different avenues through which this can occur; one would be the use of oncolytic viruses to alter the TME, another would be through the co-administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors, and yet another would be the use of small molecules that counteract the immunosuppressive cells and cytokines (Maalej et al., 2023). For example, CAR-T cells that have been modified genetically to express chemokine receptors such as CCL2b would be capable of finding their way to solid tumors that produce chemokines from those tumors or tumour-associated chemokines and would therefore be able to migrate into those solid tumors (D’Accardo et al., 2022). In addition to expressing chemokine receptors, genetically modified CAR-T cells can be engineered to secrete enzymes that degrade extracellular matrix, which would allow the CAR-T cells to penetrate the dense tumour stroma and ultimately provide greater access to target cells.

6.3. Novel CAR Designs and Combinatorial Approaches

Multi-antigen targeting strategies, such as tandem CARs or by co-administering CAR-T cells targeting different antigens, seek to reduce antigen escape and address the growing issue of tumor heterogeneity within solid tumors (Nie, 2025). Additionally to these antigen-like targeting strategies, researchers are investigating nanobody-based CAR-T cells, of which a key feature shall be the capability to effectively target highly expressed proteins found in the tumor microenvironment such as PD-L1 and fibronectin EIIIB splice variant, to restrict tumor growth (Roselli et al., 2021). The combination of both strategies will not only create a direct kill on tumor cells, but also re-structure the tumor microenvironment to create better access for CAR-T cells to enter the tumor (Andreou et al., 2025). Moreover, targeting cancer associated fibroblasts with CAR-T cells, specifically those that express fibroblast activation protein (FAP), is an additional viable approach for disrupting the immunosuppressive stromal barrier surrounding tumors, in order to aid in maximizing the efficacy of CAR-T cells (Croizer et al., 2024). Furthermore, targeting the tumor vascular network also has the potential to facilitate CAR-T cell trafficking and infiltration into tumors. Thus, the approaches mentioned may provide a greater advantage than standard CAR T cell Therapy for highly vascular solid tumors (Chen & Zhou, 2025). Pre-conditioning strategies (for instance, radiation therapy) disrupt tumor stroma networks and modify the tumor microenvironment, thereby providing additional benefits to CAR-T cell infiltration (Nie, 2025). Also, boosting T cell metabolic fitness through methods like PGC-1α over-expression for improved mitochondrial biogenesis shows promise in vitro and in vivo. These methods prevent exhaustion of T cells in laboratory settings, but there are currently no large clinical studies that demonstrate the same success, therefore current efforts focus on identifying the best metabolic profile for application in humans while maintaining safety (Ramapriyan et al., 2024). Lastly, utilizing CAR-T cell therapy with additional conventional treatments (e.g. chemotherapy) and other immunotherapeutic treatments (e.g. oncolytic viruses, immune checkpoint inhibitors, etc.) may provide synergistic effects that contribute to greater anti-tumor responses (Andreou et al., 2025). Pre-clinical combined use of CAR-T cells and anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies has demonstrated improved outcomes (Maalej et al., 2023). CAR-T cell therapy in combination with other methods addresses the challenges associated with the solid tumor microenvironment where there is competition for at least one metabolic substrate, in addition to the presence of various physical barriers that inhibit CAR T effectiveness (Kankeu Fonkoua et al., 2022).

7. Future Prospects and Emerging Technologies

7.1. Allogeneic CAR-T Cells

The use of allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy (derived from healthy donors and creating an off-the-shelf treatment option) as an alternative to autologous CAR-T cell therapies has been looked upon as another means of addressing these cost and logistical challenges (Du et al., 2025). The engineering involved with allogeneic CAR-T cells is specifically designed to reduce the risk of graft-versus-host disease and prevent host-versus-graft rejection by disrupting the T-cell receptor (TCR) gene and the human leukocyte antigen genes, which is essential for the successful clinical implementation of allogeneic CAR-T cell platforms.

7.2. In Vivo CAR Gene Delivery

The ability to introduce CAR genes directly into a patient's circulating T cells (TCRs) through in vivo approaches will minimise the number of invasive procedures required for ex vivo generation of CAR-T cells and significantly reduce costs and lead times for these procedures. The need for ex vivo manipulations, like those described by Chen and Zhou (2025), has been avoided by introducing the CAR constructs directly into the patient's circulating T cells via the use of viral and/or non-viral vectors. Although the direct introduction of CAR genes is an exciting new possibility for CAR-T cell therapy, there are still many challenges related to both the efficient and selective transfer of the CAR genes into T cells as well as ensuring that an adequate level of CAR proteins are produced by the T cells following the transfer of the CAR genes. Future research efforts will focus on the development of improved Production Methods and Novel Technologies to overcome the limitations of Current CAR-T Cell Therapy and improve the Success Rates associated with treating Solid Tumours (Ai et al., 2024).

7.3. CRISPR/Cas9 Edited CAR-T Cells

The utilization of CRISPR/Cas9 technology can be leveraged for modification of genes present in the tumor microenvironment, genes expressing T-cells, and genes regulating T-cells response to produce a more strengthened immune response against tumors (Wang et al., 2019). Specifically, using CRISPR/Cas9 allows researchers to specifically delete the inhibitory receptors PD-1 and LAG-3, thereby improving T-cell reactive (i.e., activated) response to the immunosuppressive tumor micro environment (Dagar et al., 2023). Additionally, through the ability to insert CAR-T cells into specific locations on the chromosomes, such as the TRAC locus, CAR-T cells can be produced with more consistent CAR expression and less spontaneous activation (Alnefaie et al., 2022). Moreover, the ability to generate "universal" CAR-T cells by deleting the gene coding for the TCR receptor would significantly reduce the likelihood of Graft vs Host Disease in allogeneic CAR-T cells (Zhang et al., 2024).

8. Barriers to Widespread Adoption: Manufacturing and Economics

The adoption of CAR-T therapy is limited by logistical and economic barriers in addition to the biological challenges. The autologous model currently requires manufacturing a patient-specific product through patient apheresis, ex vivo engineering and then reinfusing that product back into the patient. The current "vein-to-vein" time from apheresis to infusion is two to four weeks, a time frame during which patients with rapidly progressive disease may deteriorate (Stemer et al., 2025). The cost of producing CAR-T products is high, often exceeding $375,000 USD per dose, and the need to produce these products in specialized Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facilities, which limits access to CAR-T products to primarily major academic centers (Cliff et al., 2023).

Additionally, the use of viral vectors for CAR-T manufacturing (i.e., lentivirus and retrovirus) presents difficulties in scaling the process to meet the increased demand for CAR-T products and a significant cost driver. Future advances in CAR-T manufacturing should move toward automated, closed-system manufacturing (e.g., the "clinic-in-a-box" model) and non-viral gene editing techniques (i.e., transposon systems or CRISPR) to reduce the cost of CAR-T products and decentralize manufacture of the products (Stemer et al., 2025). In addition, the development of "off-the-shelf" allogeneic CAR-T cells that can be manufactured from healthy donors would likely provide the most feasible solution to overcome these barriers; however, issues with persistence and allo-rejection of allogeneic CAR-T cells must be addressed first (Cliff et al., 2023).

9. Conclusion

CAR-T cell therapy is on the verge of revolutionizing the way we treat cancer by establishing an entirely new standard of care for patients with relapsed B-cell malignancies in modern oncology. However, for CAR -T cells to be successfully adapted to solid Tumors will require a significant paradigm shift from simply "targeting Antigens" to "mastering the TME." As described within the review article, future success will not depend on one major technological advancement, but rather the intersection of three distinct areas of research. First, we need to develop the means to overcome TME suppression and transition away from the use of simple cytotoxicity to the engineering of "living drugs", i.e. cells that will proactively remodel the unfriendly tumor stroma via the secretion of armored cytokines and metabolic reprogramming. Second, access to CAR-T therapy will require the transition from custom autologous manufacturing to scalable, off-the-shelf allogeneic platforms in order to reduce "vein-to-vein" time and financial toxicity. Finally, there will be a requirement for the implementation of logical gated safety switches to provide precision control, removing the ability for potent anti-tumor activity to generate life-threatening systemic toxicities. Ultimately, the evolution of CAR -T therapy from a "last-line" salvage therapy to a precise, tunable, and accessible therapy in earlier phases of the treatment landscape represents the true future of CAR -T therapy. The ability to achieve this will require productive rigorously validated clinical trials evaluating these next-generation constructs in terms of not only survival but also quality of life and global access.

Conflict of Interest

The corresponding author, Zeeshan Ahmad Bhutta, serves as an Associate Editor for this journal. The authors declare that they have no other known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT Author Statement

Zeeshan Ahmad Bhutta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Ayesha Kanwal: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Tahreem Kanwal: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as it is a review of existing literature.

References

Ai, K., Liu, B., Chen, X., Huang, C., Yang, l., Zhang, W., Weng, J., Du, X., Wu, K., & Lai, P. (2024). Optimizing CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors: current challenges and potential strategies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-024-01625-7

Ali, A., & DiPersio, J. F. (2024). ReCARving the future: bridging CAR T-cell therapy gaps with synthetic biology, engineering, and economic insights. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1432799

Alnefaie, A., Albogami, S., Asiri, Y., Ahmad, T., Alotaibi, S. S., Al-Sanea, M. M., & Althobaiti, H. (2022). Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells: An Overview of Concepts, Applications, Limitations, and Proposed Solutions. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.797440

Anderson, N. R., Minutolo, N. G., Gill, S., & Klichinsky, M. (2021). Macrophage-Based Approaches for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Research, 81(5), 1201-1208. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-20-2990

Andreou, T., Neophytou, C., Kalli, M., Mpekris, F., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2025). Breaking barriers: enhancing CAR-armored T cell therapy for solid tumors through microenvironment remodeling. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1638186

Brudno, J. N., & Kochenderfer, J. N. (2024). Current understanding and management of CAR T cell-associated toxicities. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 21(7), 501-521. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-024-00903-0

Chang, Y., Chang, M., Bao, X., & Dong, C. (2024). Advancements in adoptive CAR immune cell immunotherapy synergistically combined with multimodal approaches for tumor treatment. Bioactive Materials, 42, 379-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.08.046

Chen, T., Wang, M., Chen, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). Current challenges and therapeutic advances of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Cancer Cell International, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-024-03315-3

Chen, Z., & Zhou, X. (2025). Decoding signaling architectures: CAR versus TCR dynamics in solid tumor immunotherapy. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. https://doi.org/10.3724/abbs.2025190

Cliff, E. R. S., Kelkar, A. H., Russler-Germain, D. A., Tessema, F. A., Raymakers, A. J. N., Feldman, W. B., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2023). High Cost of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells: Challenges and Solutions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 43, e397912. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_397912

Croizer, H., Mhaidly, R., Kieffer, Y., Gentric, G., Djerroudi, L., Leclere, R., Pelon, F., Robley, C., Bohec, M., Meng, A., Meseure, D., Romano, E., Baulande, S., Peltier, A., Vincent-Salomon, A., & Mechta-Grigoriou, F. (2024). Deciphering the spatial landscape and plasticity of immunosuppressive fibroblasts in breast cancer. Nature Communications, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47068-z

Cuenca, J. A., Schettino, M. G., Vera, K. E., & Tamariz, L. E. (2022). Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: A narrative review of the literature. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncolog�a, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.24875/j.gamo.M21000223

D’Accardo, C., Porcelli, G., Mangiapane, L. R., Modica, C., Pantina, V. D., Roozafzay, N., Di Franco, S., Gaggianesi, M., Veschi, V., Lo Iacono, M., Todaro, M., Turdo, A., & Stassi, G. (2022). Cancer cell targeting by CAR-T cells: A matter of stemness. Frontiers in Molecular Medicine, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmmed.2022.1055028

Dagar, G., Gupta, A., Masoodi, T., Nisar, S., Merhi, M., Hashem, S., Chauhan, R., Dagar, M., Mirza, S., Bagga, P., Kumar, R., Akil, A. S. A.-S., Macha, M. A., Haris, M., Uddin, S., Singh, M., & Bhat, A. A. (2023). Harnessing the potential of CAR-T cell therapy: progress, challenges, and future directions in hematological and solid tumor treatments. Journal of Translational Medicine, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04292-3

Devaraji, M., & Varghese Cheriyan, B. (2025). Immune-based cancer therapies: mechanistic insights, clinical progress, and future directions. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute, 37(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-025-00319-6

Du, B., Qin, J., Lin, B., Zhang, J., Li, D., & Liu, M. (2025). CAR-T therapy in solid tumors. Cancer Cell, 43(4), 665-679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2025.03.019

El-Daly, S. M., & Hussein, J. (2019). Genetically engineered CAR T-immune cells for cancer therapy: recent clinical developments, challenges, and future directions. Journal of Applied Biomedicine, 17(1), 11-11. https://doi.org/10.32725/jab.2019.005

Ercilla-Rodríguez, P., Sánchez-Díez, M., Alegría-Aravena, N., Quiroz-Troncoso, J., Gavira-O'Neill, C. E., González-Martos, R., & Ramírez-Castillejo, C. (2024). CAR-T lymphocyte-based cell therapies; mechanistic substantiation, applications and biosafety enhancement with suicide genes: new opportunities to melt side effects. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1333150

Guzman, G., Reed, M. R., Bielamowicz, K., Koss, B., & Rodriguez, A. (2023). CAR-T Therapies in Solid Tumors: Opportunities and Challenges. Current Oncology Reports, 25(5), 479-489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-023-01380-x

Huang, Z., Dewanjee, S., Chakraborty, P., Jha, N. K., Dey, A., Gangopadhyay, M., Chen, X.-Y., Wang, J., & Jha, S. K. (2023). CAR T cells: engineered immune cells to treat brain cancers and beyond. Molecular Cancer, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01712-8

Jaing, T.-H., Hsiao, Y.-W., & Wang, Y.-L. (2025). Chimeric Antigen Receptor Cell Therapy: Empowering Treatment Strategies for Solid Tumors. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47020090

Jutzi, J. T., Wampfler, J., Ionescu, C., Kronig, M. N., Jeker, B., Hoffmann, M., Reusser, I., Haslebacher, C., Sendi Stamm, S., Schletti, M., Lüscher, B. P., Bacher, V. U., Wehrli, M., Daskalakis, M., Pabst, T., & Novak, U. (2025). CAR T‐Cell Therapies for Patients With Relapsed and Refractory Aggressive Lymphomas: Real‐World Experiences From a Single Center on the Use of Radiotherapy. Hematological Oncology, 43(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.70124

Kankeu Fonkoua, L. A., Sirpilla, O., Sakemura, R., Siegler, E. L., & Kenderian, S. S. (2022). CAR T cell therapy and the tumor microenvironment: Current challenges and opportunities. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics, 25, 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2022.03.009

Kaur, S. D., Abubakar, M., Bedi, N., Rao puppala, E., Kapoor, D. N., Kumar, N., Ahemad, N., & Anwar, S. (2025). Current perspectives on Lifileucel tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy: A paradigm shift in immunotherapy. Current Problems in Cancer, 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2025.101252

Kosti, P., Maher, J., & Arnold, J. N. (2018). Perspectives on Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Immunotherapy for Solid Tumors. Frontiers in Immunology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01104

Leyfman, Y. (2018). Chimeric antigen receptors: unleashing a new age of anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Cell International, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-018-0685-x

Li, J., Li, W., Huang, K., Zhang, Y., Kupfer, G., & Zhao, Q. (2018). Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) immunotherapy for solid tumors: lessons learned and strategies for moving forward. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0568-6

Liang, Y. (2021). Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in cancer: Advances and challenges. Aging Pathobiology and Therapeutics, 3(3), 46-47. https://doi.org/10.31491/apt.2021.09.062

Liu, Z., Lei, W., Wang, H., Liu, X., & Fu, R. (2024). Challenges and strategies associated with CAR-T cell therapy in blood malignancies. Experimental Hematology & Oncology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-024-00490-x

Lu, L., Xie, M., Yang, B., Zhao, W. B., & Cao, J. (2024). Enhancing the safety of CAR-T cell therapy: Synthetic genetic switch for spatiotemporal control. Sci Adv, 10(8), eadj6251. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj6251

Luo, J., & Zhang, X. (2024). Challenges and innovations in CAR-T cell therapy: a comprehensive analysis. Frontiers in Oncology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1399544

Maalej, K. M., Merhi, M., Inchakalody, V. P., Mestiri, S., Alam, M., Maccalli, C., Cherif, H., Uddin, S., Steinhoff, M., Marincola, F. M., & Dermime, S. (2023). CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Molecular Cancer, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01723-z

Nasiri, F., Farrokhi, K., Safarzadeh Kozani, P., Mahboubi Kancha, M., Dashti Shokoohi, S., & Safarzadeh Kozani, P. (2023). CAR-T cell immunotherapy for ovarian cancer: hushing the silent killer. Frontiers in Immunology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1302307

Neelapu, S. S., Jacobson, C. A., Ghobadi, A., Miklos, D. B., Lekakis, L. J., Oluwole, O. O., Lin, Y., Braunschweig, I., Hill, B. T., Timmerman, J. M., Deol, A., Reagan, P. M., Stiff, P., Flinn, I. W., Farooq, U., Goy, A. H., McSweeney, P. A., Munoz, J., Siddiqi, T.,…Locke, F. L. (2023). Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood, 141(19), 2307-2315. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022018893

Nie, Y. (2025). Breaking barriers: the emerging promise of CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors. Holistic Integrative Oncology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44178-025-00205-0

Poojary, R., Song, A., Song, B., Song, C., Wang, L., & Song, J. (2023). Investigating chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy and the potential for cancer immunotherapy (Review). Molecular and Clinical Oncology, 19(6). https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2023.2691

Qu, C., Zhang, H., Cao, H., Tang, L., Mo, H., Liu, F., Zhang, L., Yi, Z., Long, L., Yan, L., Wang, Z., Zhang, N., Luo, P., Zhang, J., Liu, Z., Ye, W., Liu, Z., & Cheng, Q. (2022). Tumor buster - where will the CAR-T cell therapy ‘missile’ go? Molecular Cancer, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01669-8

Ramapriyan, R., Vykunta, V. S., Vandecandelaere, G., Richardson, L. G. K., Sun, J., Curry, W. T., & Choi, B. D. (2024). Altered cancer metabolism and implications for next-generation CAR T-cell therapies. Pharmacol Ther, 259, 108667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2024.108667

Ramos, C. A., Heslop, H. E., & Brenner, M. K. (2016). CAR-T Cell Therapy for Lymphoma. Annual Review of Medicine, 67(1), 165-183. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-051914-021702

Rodriguez-Garcia, A., Palazon, A., Noguera-Ortega, E., Powell, D. J., & Guedan, S. (2020). CAR-T Cells Hit the Tumor Microenvironment: Strategies to Overcome Tumor Escape. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01109

Roselli, E., Faramand, R., & Davila, M. L. (2021). Insight into next-generation CAR therapeutics: designing CAR T cells to improve clinical outcomes. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 131(2). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci142030

Ruella, M., Korell, F., Porazzi, P., & Maus, M. V. (2023). Mechanisms of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor-T cells in haematological malignancies. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 22(12), 976-995. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-023-00807-1

Sahlolbei, M., Ahmadieh-Yazdi, A., Rostamipoor, M., Manoochehri, H., Mahaki, H., Tanzadehpanah, H., Kalhor, N., & Sheykhhasan, M. (2024). Recent Updates on Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Approaches in Cancer Immunotherapy. In Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1005116

Satapathy, B. P., Sheoran, P., Yadav, R., Chettri, D., Sonowal, D., Dash, C. P., Dhaka, P., Uttam, V., Yadav, R., Jain, M., & Jain, A. (2024). The synergistic immunotherapeutic impact of engineered CAR-T cells with PD-1 blockade in lymphomas and solid tumors: a systematic review. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1389971

Schroeder, T., Martens, T., Fransecky, L., Valerius, T., Schub, N., Pott, C., Baldus, C., & Stölzel, F. (2024). Management of chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell-associated toxicities. Intensive Care Medicine, 50(9), 1459-1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-024-07576-4

Schwerdtfeger, M., Benmebarek, M.-R., Endres, S., Subklewe, M., Desiderio, V., & Kobold, S. (2021). Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified T Cells and T Cell–Engaging Bispecific Antibodies: Different Tools for the Same Job. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports, 16(2), 218-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-021-00628-2

Sriwastava, A., Gupta, S., Kumar, A., Gupta, S., & Kumar, D. (2024). CAR-T Cells: A Breakthrough in Cancer Treatment. In Biology of T Cells in Health and Disease. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1005110

Stemer, G., Mittermayr, T., Schnell-Inderst, P., & Wild, C. (2025). Costs, challenges and opportunities of decentralised chimeric antigen receptor T-cell production: a literature review and clinical experts' interviews. Eur J Hosp Pharm, 32(3), 202-208. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2024-004130

Sterner, R. C., & Sterner, R. M. (2021). CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer Journal, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7

Sun, D., Shi, X., Li, S., Wang, X., Yang, X., & Wan, M. (2024). CAR‑T cell therapy: A breakthrough in traditional cancer treatment strategies (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2024.13171

Sun, R., Lei, C., Xu, Z., Gu, X., Huang, L., Chen, L., Tan, Y., Peng, M., Yaddanapudi, K., Siskind, L., Kong, M., Mitchell, R., Yan, J., & Deng, Z. (2024). Neutral ceramidase regulates breast cancer progression by metabolic programming of TREM2-associated macrophages. Nature Communications, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45084-7

Tufail, M., Jiang, C.-H., & Li, N. (2025). Immune evasion in cancer: mechanisms and cutting-edge therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02280-1

Uslu, U., & June, C. H. (2024). Beyond the blood: expanding CAR T cell therapy to solid tumors. Nature Biotechnology, 43(4), 506-515. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02446-2

Wang, Z., Chen, W., Zhang, X., Cai, Z., & Huang, W. (2019). A long way to the battlefront: CAR T cell therapy against solid cancers. Journal of Cancer, 10(14), 3112-3123. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.30406

Yu, T., Jiang, W., Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., Jiao, J., & Wu, M. (2024). Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in the treatment of osteosarcoma (Review). International Journal of Oncology, 64(4). https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2024.5628

Zafar, A., Khan, M. J., Abu, J., & Naeem, A. (2024). Revolutionizing cancer care strategies: immunotherapy, gene therapy, and molecular targeted therapy. Molecular Biology Reports, 51(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-09096-8

Zhang, T., Zhang, Y., & Wei, J. (2024). Overcoming the challenges encountered in CAR-T therapy: latest updates from the 2023 ASH annual conference. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1389324

Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Zhang, H., Chen, S., & Xiao, Y. (2022). CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Current Opportunities and Challenges. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.927153

Zhang, Y., Hu, R., Xie, X., & Li, Y. (2025). Expanding the frontier of CAR therapy: comparative insights into CAR-T, CAR-NK, CAR-M, and CAR-DC approaches. Annals of Hematology, 104(9), 4305-4317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-025-06538-0

Zhong, Y., & Liu, J. (2024). Emerging roles of CAR-NK cell therapies in tumor immunotherapy: current status and future directions. Cell Death Discovery, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02077-1

Zhu, J., Zhou, J., Tang, Y., Huang, R., Lu, C., Qian, K., Zhou, Q., Zhang, J., Yang, X., Zhou, W., Wu, J., Chen, Q., Lin, Y., & Chen, S. (2025). Advancements and challenges in CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors: A comprehensive review of antigen targets, strategies, and future directions. Cancer Cell International, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-025-03938-0